Welcome to English Teacher Weekly—your source for what’s worthwhile from the worlds of literature, education, Christian thought, and the humanities.

If you’re an English teacher—or simply enjoy English teacher vibes—this newsletter is for you.

For the next four weeks I’m running a Back to School Special: become a paid subscriber to ETW for half the regular cost! If you’d like to support ETW and all the work that goes into it, but the $50/year rate is a little too steep for your budget, now is your time. The paid subscribers keep this train rolling. You’ll have access to the complete archives and every edition of ETW—and most importantly—you’ll experience the sweet, sweet sensation of patronage.

Thanks!

This week’s edition is for paid subscribers, but don’t be afraid. The majority of ETW’s editions will remain open to all readers.

THIS WEEK’S FEATURES

Tennis and Literature

In honor of the US Open this past weekend, I raided the NYT archives and came back with some real aces. We’ll start with David Foster Wallace, widely known for his fierce backhand.

From 2006, “Roger Federer as Religious Experience” (gift link):

Beauty is not the goal of competitive sports, but high-level sports are a prime venue for the expression of human beauty. The relation is roughly that of courage to war.

The human beauty we’re talking about here is beauty of a particular type; it might be called kinetic beauty. Its power and appeal are universal. It has nothing to do with sex or cultural norms. What it seems to have to do with, really, is human beings’ reconciliation with the fact of having a body.

And here’s a brief observation from poet Philip Levine on Rafael Nadal’s command of the court. From 2011:

“On TV, it sometimes seems as though Nadal is angry at his opponent. Maybe the camera is too close. But watching him out there, he seems quietly thrilled with his remarkable gifts. On TV, you don’t realize how big the court is. Out there on his own, he is very human. Very beautiful.”

And, finally, Jeffery Meyers catalogs the long history of poets’ love of tennis, covering Hemingway, Kunitz, Berryman, and more. From 1985:

Tennis provided three generations of American poets with an outlet for aggression. They carried their inflated egos from the study to the court and competed as ruthlessly in sporting as in literary life. Robert Frost, who had a lifelong passion for the game, remarked in his attack on Carl Sandburg's defense of modernistic poetry that writing free verse was like playing tennis with the net down. And he told an interviewer: ''I've always thought of poetry as something to win or lose - a kind of prowess in the world of letters played with the most subtle and lethal of weapons.'' At the Bread Loaf School in Vermont, young writers were expected to defer to the vanity of the aging bard and gracefully accept defeat on the court.

The most flamboyant and freakish player was Ezra Pound, who sported an enormous floppy beret to distract his opponent as well as to shade his eyes. Ford Madox Ford, a sometime opponent, who was famous for his tall stories, provided an endocrinological explanation of Pound's behavior: ''Mr. Pound is an admirable, if eccentric, performer of the game of tennis. To play against him is like playing against an inebriated kangaroo that has been rendered unduly vigorous by injection of some gland or other. Once he won the tennis championship of the south of France, and the world was presented with the spectacle of Mr. Pound in a one-horse cab beside the Maire of Perpignan . . . followed by defeated tennis players, bull-fighters, banners and all the concomitants of triumph in the south.'' Pound later played regularly with visitors and staff while confined in Washington to St. Elizabeth's Hospital for the insane.

The Poetry of Luke Harvey

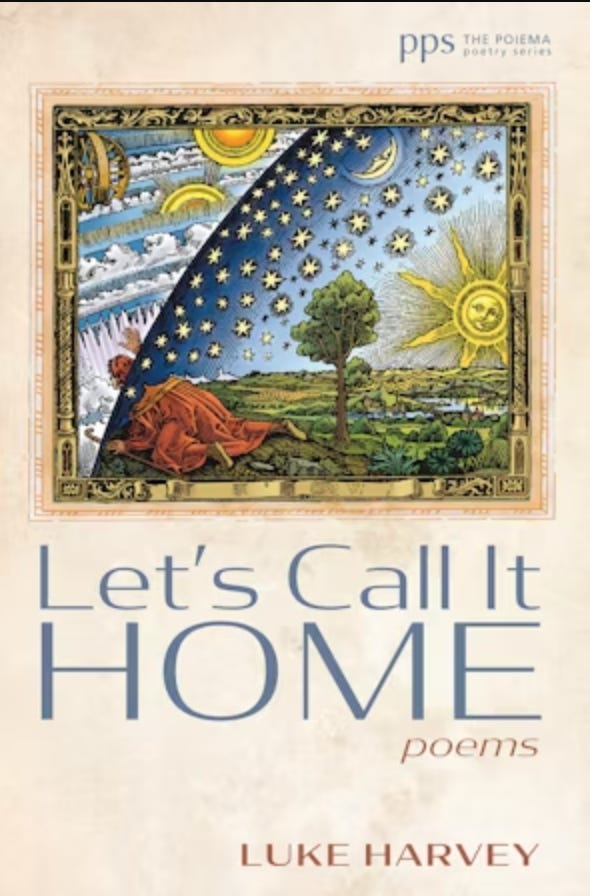

Luke Harvey’s first collection of poems was just published last week. Mine is in the mail.

Here’s some praise for the collection from poet Malcolm Guite:

Let’s Call It Home is a deft, delicate, carefully assembled collection of poems, each giving a focus and an insight of its own, but altogether intended to take you on a slow journey, an ascent and descent, a venturing out and a return. Time and again these poems do what poetry does best: they transfigure the familiar and so reveal something of its meaning: from the child crawling inch by inch towards a patch of light on the floor to the man holding the body of God inexplicably in his hand.

And here’s a sample from the collection:

Tuesday Morning, Thirtieth Week of Ordinary Time All Hallows' Eve Dead deer, already dead, again smeared a few yards ahead on the aftermarket grill-guard of a jacked-up truck in North Georgia dark. Intermittently visible in hazard lights, the old man shuffles to my window, lights, says he's "shook a bit but other than that ok." To hear him tell it, "on my way to the Snak-Shak to get a sausage biscuit when smack," left bumper, and that was that. A semi punctuates his words and divides the deer in half. We turn to look. At this point I'm late for work and unclear anymore what the work is, or if I'm doing it, but there's a long trail of blood and a road ahead.

Moments of Genuine Connection

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to English Teacher Weekly to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.